In Out of Africa, movie Karen, Baroness Blixen, is cast as a European settler who forces her culture and will on the native people. Instead, Denys Finch Hatton appropriates the real Karen, Baroness Blixen’s, compassion and grief over the changes European settlers force on the Kenyans, their culture, their identity, and their dignity.

It is a pity that Hollywood got her {deliberately}wrong.

One must wonder what this woman, who spent her life writing and wondering about the role of fate in controlling human lives would have thought of this throw of the dice?

Of course, two of her stories also won Oscars during this period of the eighties. Babette’s Feast (1986), set in the 19th-century Scandinavian village and Out of Africa(1987).

But we are getting ahead of our story. Karen would have hated that.

In 1934 the Book of the Month Club issued a curious collection by Random House in America. Seven Gothic Tales had been written by a mysterious foreigner by the name of Isak Dinesen. The stories were beautifully crafted, complicated, convoluted, enigmatic, occasionally erotic and violent and very, very unexpected. The American public’s imagination was comprehensively seized.

Four years later a new book by Isak Dinesen appeared. Can you imagine the response to the lyrically nostalgic Out of Africa when readers learned that the creator of their new obsession was none other than a Danish Baroness? Not only was their writer aristocratic, but she was also a woman.

Almost a century later the gasp still echoes audibly.

One of the first writers to describe Africans extensively, the writer remained an enigma. She was a participant in the colonial machine but was she a racist?

Moreover, her memoir left many more pressing questions unanswered.

And readers would have to wait until after her death in 1962 before their curiosity could be satisfied. Somewhat.

The things we do know

Born on the 17th of April in 1885 at the family estate in Rungstedlund north of Copenhagen on the Oresund, Karen’s parents were Wilhelm and Ingeborg.

Wilhelm was a retired soldier from a wealthy family, a landowner, sportsman, writer, and Danish parliamentarian. He traveled to Wisconsin where he lived among and studied Native Americans.

Ingeborg was the daughter of a wealthy ship owner. She was also an activist, a strong Unitarian (in a country where the religion was Lutheranism) and the first woman elected to the Rungsted parish council.

The family was connected to the royal circle but not titled. Both her father and mother’s clans had strong opinions on cultural ethics and high society was not a priority.

When Karen was 10 her father committed suicide. It is thought that he did this due to a fear of his syphilis leading to madness.

Karen studied French in Switzerland with her mother and sisters following her father’s death. She also attended art school (her writing would be influenced by her love of painting) and published her first stories at the age of 22.

Her work would emphasize the power of the public persona that reveals the hidden personality. Karen loved telling stories in her low, husky voice and would do so at any opportunity… even during a dramatic visit to the United States.

She traveled to Africa, by ship from Naples, in 1913 to join her fiance. Bror Blixen, her second cousin, was the brother of her first love. They would marry in 1914 when Karen was 28 and start a coffee plantation together.

During the Great War Karen accompanied supplies for the colonial army.

In 1915 she returned to Denmark with syphilis contracted from her husband. She is back in Africa in 1916 and buys a second farm (financed by her family). In 1918 she meets English hunter Denys Finch Hatton but returns to Denmark for a year and a half again, soon afterward. Back in Kenya in 1921, she separates from Bror.

In 1922 Karen miscarries Finch Hatton’s baby. The coffee factory burns down in 1923 and by 1924 Denys is living with her whenever he is in Nairobi. Officially divorced from Bror in 1925 she returns to Denmark for 18 months. There might have been another miscarriage in 1926, but the first cracks in her relationship with Denys now appear. Beryl Markham, a close friend of both, would claim that Finch Hatton was gay.

1927 is a good year and in 1928 Karen’s ex-husband and her lover take the Prince of Wales on Safari. Karen spends much of 1929 in Denmark, visiting Denys in England. In 1930 the coffee farm is suffering severely under the worldwide depression. On September 20 of that year, Denys takes Karen up in his airplane. Within eight months her farm is sold and Finch Hatton is killed in an airplane accident.

Karen had frequently been homesick in Africa. During the 18 years she spent on the continent she was in Denmark for five years.

When she leaves Africa in 1931 at the age of 46, Karen Blixen never returns.

Seven Gothic Tales is published in 1934 followed by Out of Africa in 1937 and Winter’s Tales in 1942. She helps to smuggle Jews out of German-occupied Denmark during the Second World War.

She undergoes spinal surgery for her abdominal pain in 1946 and in 1955 she has the gastric ulcer surgery. Inbetween the two surgeries she loses the Nobel Prize for Literature to Ernest Hemingway.

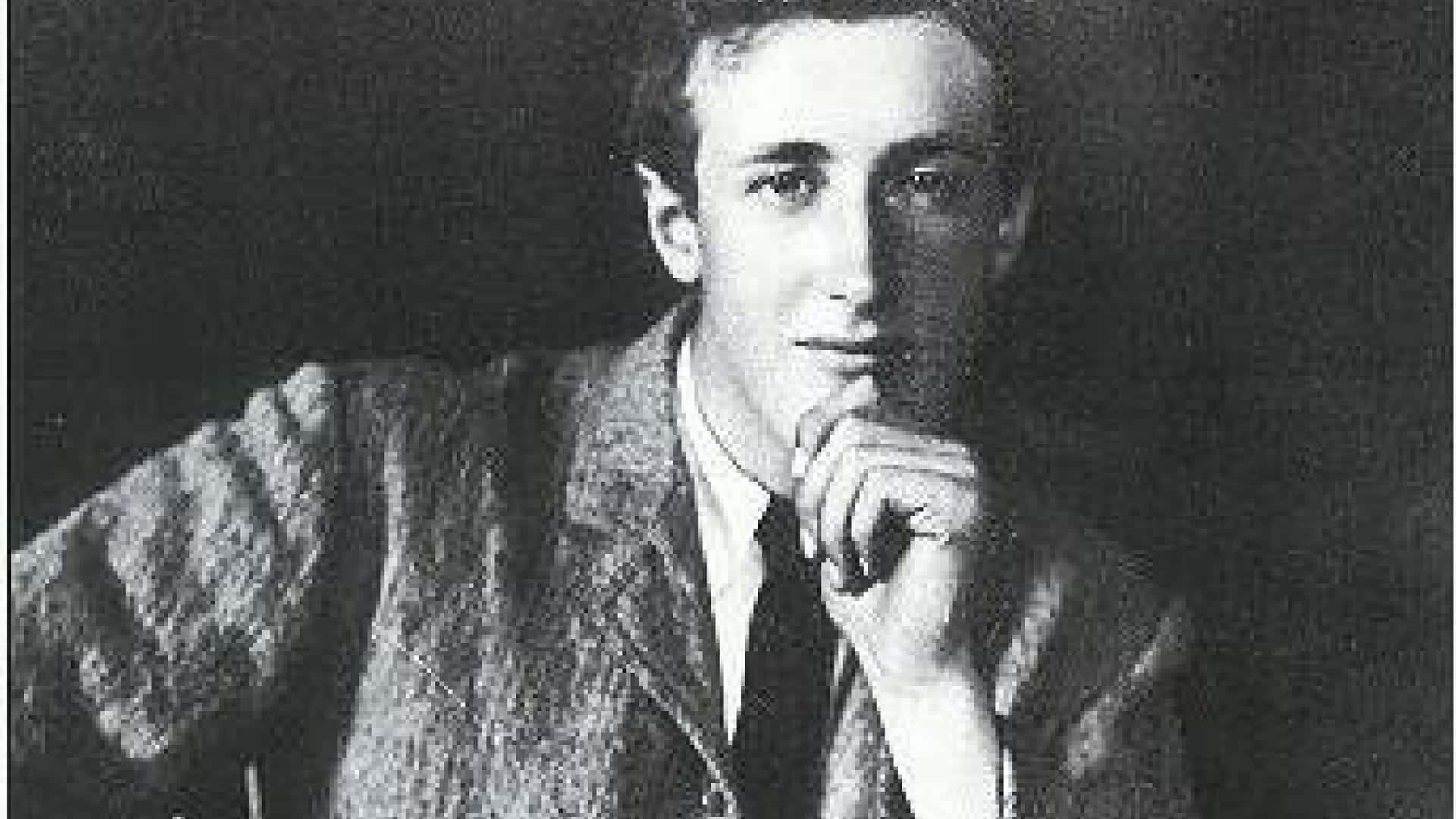

Ernest Hemingway

“I would have been happy, happier, today if the [1952] prize had been given to that beautiful writer Isak Dinesen.”

In 1957 she would lose again…. this time to Albert Camus. She takes a high-profile trip to the United States in 1959.

She was dependent on her family for financial help during all of her life. A campaign asking her supporters for money resulted in the creation of the Rungstedlund Foundation which now oversees her 40-acre property as a museum and bird reserve.

Her health

When diagnosed with syphilis at the age of 29 she received cutting-edge treatment of mercury, arsenic and fever baths. There was no sign of syphilis in her health records later in life but she might have suffered from heavy metal poisoning. She also had a gastric ulcer and had to have a third of her stomach removed. Malnutrition that resulted from the surgery caused her to grow terribly thin. Of course, her heavy smoking habit did not help.

On the 7th of September 1962, she dies, at home in Rungstedlund, from malnutrition due to her stomach surgery.

Her Deal with the Devil

Karen was a complex person and there was a wild side to her. She had her dark days, especially when she was ill. She might have been addicted to painkillers which added another dimension to her personality.

Karen fell in love with the much younger Danish poet, Thorkild Bjørnvig, late in life. The relationship, based on mutual admiration, remained platonic. Karen told him that when she was terribly sick with syphilis she made a pact with the Devil to turn all her life experiences into great stories. In Karen’s mind, there was a connection between artistic practice and pain. She demanded creativity from her physical torment.

Losing her soul to the Devil to enable her to write soulfully was a good deal. The Devil kept his promise and Blixen would refer to the incident as ‘the pact’ in her letters.

What they never told you in the movie

“Barua a Soldani” means “letter from a King.”

Karen Blixen received a letter from Danish King Christian X as thanks for a lion-skin she had sent him. When inspecting her land one day, she found a young man from the Kikuyu tribe whose leg had been crushed under a felled tree. As she did not have any morphine with her, she decided to place the King’s letter on the young Kikuyu’s chest and tell him that a letter from a king ‘will do away with all pain.’ It worked, and from that day onward the King’s ‘miracle-working’ letter became part of her medicine stock. It was used so often that it gradually became, in Blixen’s words, ‘brown and stiff with blood and matter of long ago.’

Blixen was an incredible artist and adored arranging flowers

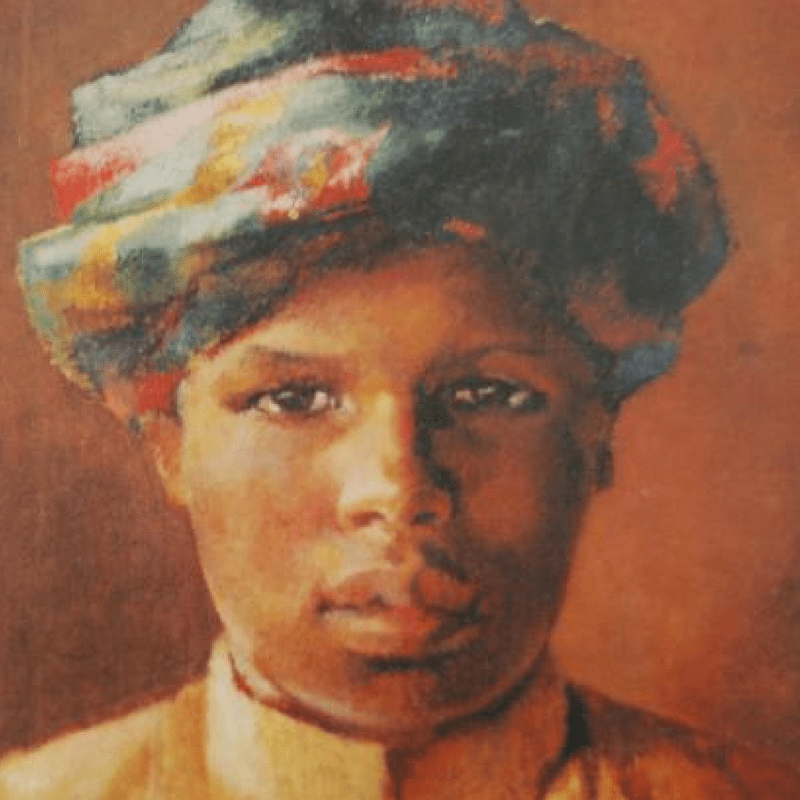

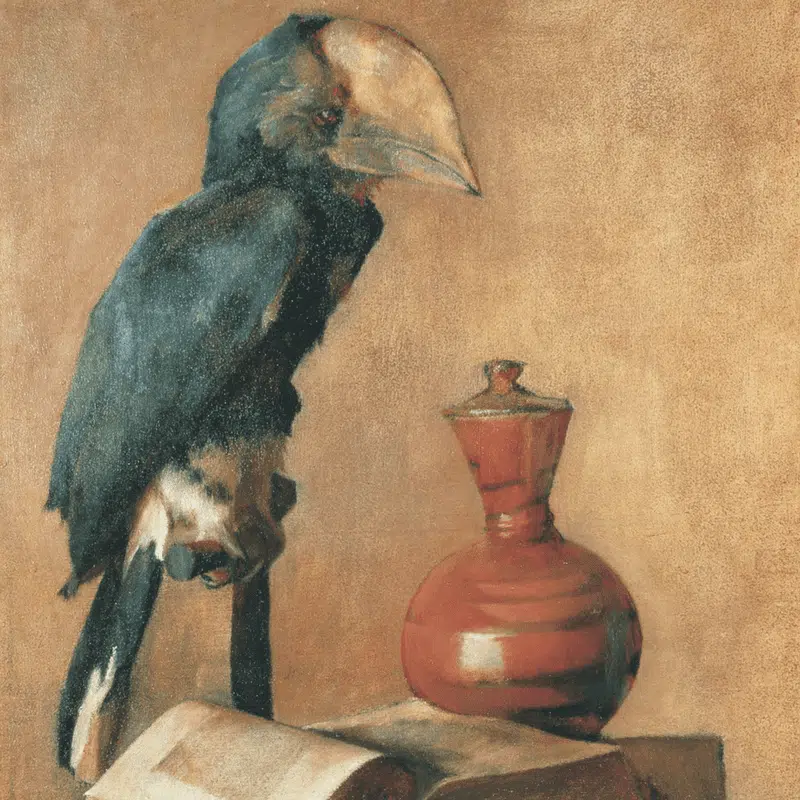

Art was her first love. In 1902, at the age of 17, she took classes at the private drawing school of Charlotte Sode and Julie Meldahl in Copenhagen, and the following year she was accepted by the newly established women’s school at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts. Her most well-known artworks are Young Kikuyu Girl and Abdullahi Ahamed.

She called her house in Kenya ‘Bogani’ or ‘Mbogani’ meaning ‘a house in the woods.’

About her words

She wrote in English and her work was translated into Danish. Her voice was formed by her Scandinavian roots, her emphasis was on the story rather than the characters and she enjoyed the philosophical examination of personal identity. The Scandinavian obsession with the role of fate can be found throughout and she believed a person’s response to their fate offered the possibility for heroism and ultimately immortality.

Karen’s Literary Influences

- Jane Austen

- Charlotte Brontë

- Edgar Allan Poe

- William FaulknerSoren Kierkegaard: at least thirteen of Isak Dinesen’s tales are based, in part, on stories by the great Danish philosopher.

- The Viking Sagas

- Shakespeare’s plays

- Mary Shelley

- Percy Bysshe Shelley

- Lord Byron

- Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey

- Mozart’s Don Juan

- Milton’s Paradise Lost

- Charles Baudelaire

- Samuel Taylor Coleridge

- Walt Whitman

- Goethe

- Nietzche

- Heinrich Heine

- Havamal, the bible of the pagan Scandinavian cosmos

- The Greek myths

- The Thousand and One Nights (The Arabian Nights)

- The Old and The New Testament

- A.E. Housman