AFRICAN TRIBES

The Himba of Namibia

There is more to the Himba than meets the eye.

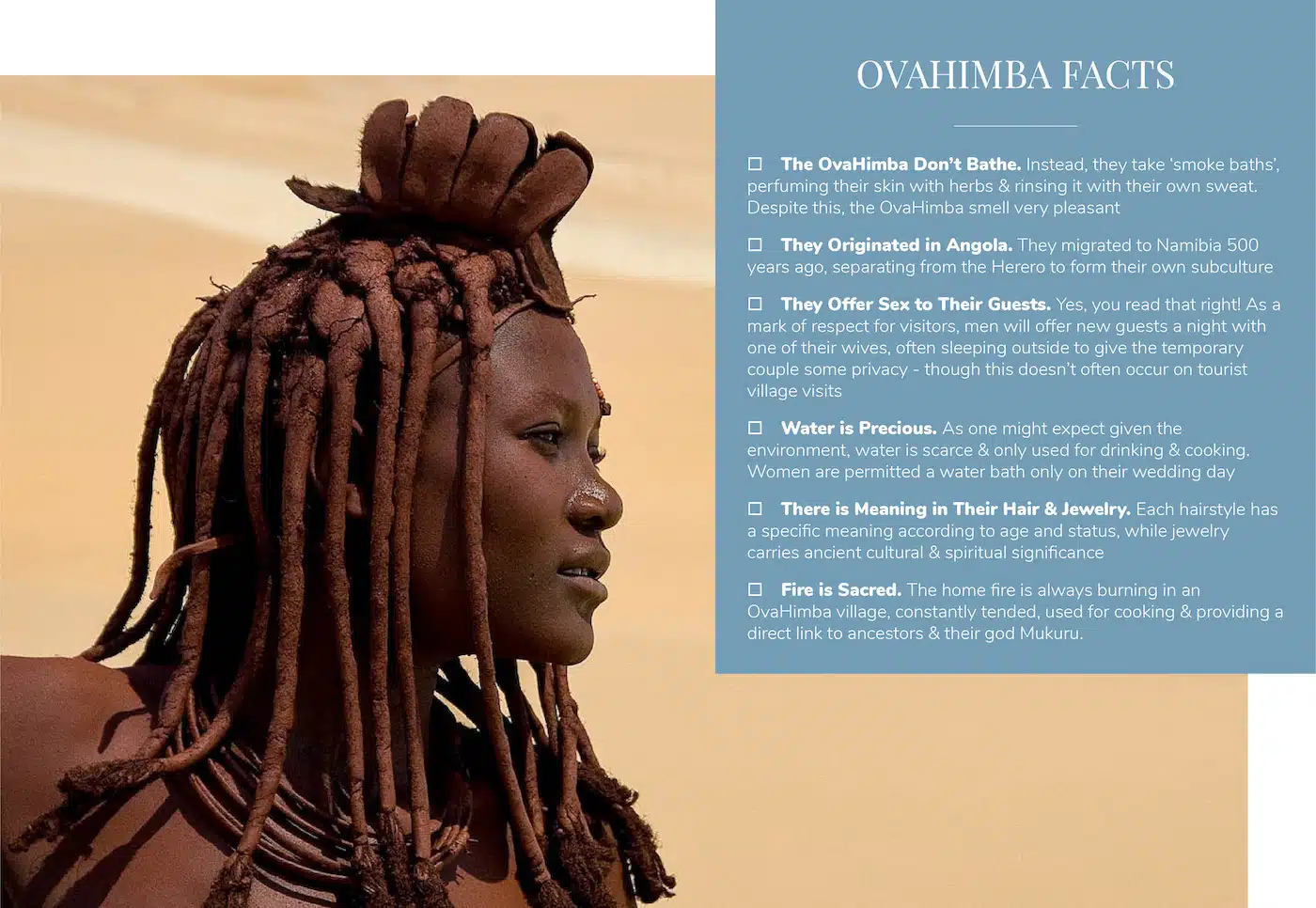

But you may be forgiven if the Himba tribe has you awestruck. Their statuesque beauty, ochre skin, and intricate accessories have captured the imagination of visitors for centuries.

Today, they are one of the most fascinating, studied and instantly recognizable tribes on the African continent. But as with many of us, much of their story lies, like an iceberg, in the history that lies under the present.

Birth of a Tribe

Five hundred years ago the Herero people moved from Angola to the Kunene region of what is now Namibia and with this move, they entered our history books. A large shortage of cows due to a relentless bovine epidemic at the end of the 19th century split the tribe into two very distinctive groups. While the part of the tribe that is still known as the Herero would move south to explore new regions in an effort to enhance their chance of survival and eventually conformed more over time, the other group called the OvaHimba held fast to their territory, their traditions, and customs. While the two groups continue to share the Herero language, the OvaHimba dialect is now known as OtjiHimba.

Though ‘Himba’ is commonly used in the West, OvaHimba is the more correct term, as when freely translated from the Otjiherero language, Himba means ‘beggar’.

Around 50,000 OvaHimba continue to live in the Kunene region in Namibia and across the Kunene River in Angola. There is a hunter-gatherer offshoot of the Himbas known as the OvaTwa but the OvaHimba are Namibia’s last semi-nomadic pastoralists.

There are Three Distinct Aspects of a Himba Woman’s Look

OvaHimba Women are Red

The natural environment of the OvaHimba is hot and semi-arid. Clothes consist of a simple skirt made from calfskin (modern materials are becoming increasingly popular) and they sometimes wear sandals, often crafted from discarded car tires. The distinctive color of female (and some male) members of the tribe is courtesy of a cosmetic mixture of butterfat and ochre pigment (pounded hematite stone) that is perfumed with aromatic omuzumba shrub resin and applied to their bodies. There is a good reason for the otjize paste as it protects them from the harsh sun, the arid atmosphere and mosquito bites. Despite this, cultural beauty is a significant motivation for daubing their skin in this deep orange paste. It also keeps skin clean and moist and is known to block hair growth. Otjize also gives the OvaHimba hair a characteristic texture and style. It is the ultimate OvaHimba ideal of beauty, symbolizing the earth’s life-giving color and the hue of blood – the essence of life.

Their Hair Extensions are Extraordinary

The OvaHimba women sport hair extensions that are often made from goat hair gathered from the livestock they breed. The tribe also breeds fat-tailed sheep and will occasionally cattle – a significant sign of their wealth. The livestock provides milk and meat which is consumed together with the rain-fed maize and millet they farm. The OvaHimba diet also includes chicken eggs, wild herbs, and honey. The style of hair extension can signal age and social status.

All OvaHimba start life with bald heads and will regularly have their heads entirely shaved or sometimes a small patch on the crown is allowed to grow. Hair is plaited to the rear of the head for young boys and little girls have two braided hair plaits that are angled towards the face at the level of their eyes, while twins may have one braided hair plait extending forwards. Patrilineal descent (oruzo membership) will determine the exact style that they will keep until they reach puberty.

At the onset of puberty, girls will start adding otjize-textured hair plaits that can be arranged to veil the girl’s face. Hair plaits can also be tied together and held parted back from the face.

The Erembe style of headdress is only worn by girls or women who have been married for approximately a year or who have had a child. OvaHimba women are married into arranged wedlock as soon as they reach puberty and on average this polygamous tribe’s men will have two wives. The practice of marrying girls as young as 10 to partners chosen by their fathers is illegal in Namibia and the OvaHimba themselves are increasingly opposed to the practice, though it still remains widespread. The Erembe is sculptured from sheepskin and many plaits of hair, all colored and held in place by otjize. The OvaHimba use wood ash to cleanse their hair as water is an extremely scarce and precious commodity.

No one is allowed to use the scarce water for washing and so OvaHimba women will take a daily smoke bath to maintain personal hygiene. This is practiced by placing smoldering charcoal into a small bowl of herbs such as leaves and branches of the Commiphora tree and when the smoke starts rising one bows over the bowl until perspiring. To wash the entire body, the OvaHimba cover themselves in a blanket to trap the smoke and heat under the fabric.

Boys are circumcised before puberty and considered a man once they are married, while girls only become true women once they have given birth.

The Himba Craft Beautiful & Intricate Jewelry

OvaHimba women are physically extremely active, even more so than the men and boys of the tribe. They will carry water, cover the mopane wood homes of the homestead (onganda) with earthen plaster made up of red clay soil and cow manure, collect firewood, tend to the calabash vines, milk the cows and goats to create soured milk, cook and serve meals, raise the new members of the tribe… and they somehow still find time to make exquisite jewelry, handicrafts, and clothes.

The women wear a large number of necklaces and arm bracelets crafted from ostrich eggshell beads, grass, cloth, and copper. An individual’s adornments can weigh up to 90lb (40kg).

An OvaHimba woman’s most private part of the body is her ankles and these are covered by a sleeve of iron bracelets.

Himba Religion & Politics

The OvaHimba are monotheistic animists and their God Mukuru, the sacred ancestral fire (okuruwo) and their sacred livestock completes the Trinity at the center of each family’s universe. The women prepare incense from aromatic herbs and resins and use the smoke as an antimicrobial body wash, deodorant, and fragrance. Wood to feed the ever-smoldering fire is always ready on the sacred stone next to the fire.

On behalf of the family, the fire-keeper will approach the sacred ancestral fire around once a week to communicate with Mukuru and the ancestors who act as Mukuru’s representatives when the God himself is otherwise occupied. Communication happens through the smoke, transported on the holy fire rising into the heavens.

Outsiders or anyone who has not received an invitation to visit an OvaHimba village may not cross the holy line running from the main entrance to the chief’s hut in a direct line past the holy fire and to the entrance of the cattle enclosure.

The OvaHimba are also strong believers in omiti – what we loosely understand under the definition of witchcraft. This belief transfers substantial power to traditional African healers.

The Harsh Himba History

It has not only been the usual elements and severe occasional drought that have tested the OvaHimba.

The tribe was subjected to the last century’s first attempt at racial extermination between 1904-1908 when the German Empire under Lothar von Trotha attempted to commit genocide against the Ovaherero, the Nama and the San.

A perfect storm in the 1980s pitted the tribe against a double threat of severe drought (killing 90 percent of their livestock) and being the pawns of political conflict in the South African Border War with Angola.

And yet, the OvaHimba are still standing strong today. They are incredibly remarkable for expertly managing the tenacity with which they cling to their culture in tandem with acting in a thoroughly modern context such as successfully working with international activists to block the proposed hydroelectric dam threatening to flood their ancestral lands.

They are also campaigning against culturally inappropriate schools for their children and the detainment of Ovatwa in secured camps in northern Kunene. The OvaHimba can be found issuing declarations to the African Union and the OHCHR on violations of civil, cultural, economic, environmental, social and political rights. In an excellent example of their adherence to culture in unity with their participation in modern cultural affairs, they protested against a German reality TV show misusing and mocking their culture.

A World in Only Four Colors

The OvaHimba perception of color is interesting. They recognize only four hues.

- Zuzu encompasses all dark shades of blue, red, green and purple.

- Vapa is white and some yellows

- Buru is some greens and blues

- And dambu refers to lighter shades of green, red and brown.

Meet the Himba: Namibia Itineraries

Porridge is Himba life

The OvaHimba will rarely eat meat. Twice a day they will boil water, add maize or occasionally mahangu (pearl millet) flour and oil to prepare their staple porridge.

Eggs and milk are also consumed, though again, these are only eaten sparingly.

A Cultural Conundrum

It is thought that the OvaHimba retained their traditions due to living in one of the most extreme environments on earth and their subsequent seclusion from other external influences. But the OvaHimba’s adherence to their culture becomes only more remarkable when one realizes how socially dynamic they are.

They do not isolate themselves from local urban culture and coexist with members of Namibia’s other ethnic groups quite easily. They will happily shop in a supermarket, consume modern food and use modern healthcare before returning to their own way of life and cultural foundations.

The tribal structure is based on bilateral descent which has every clan member belonging both to their own matriarchal and patriarchal clan. Clans are led by the eldest male member and daughters will live with their husband’s clan after marriage. Inheritance, on the other hand, is determined by matrilineal means with a son inheriting his maternal uncle’s cattle rather than his father.

A system of bilateral descent is rare and found only in West Africa, India, Australia, Melanesia, and Polynesia – always in harsh environments.

Discover the Himba

Africa is possessed of numerous fascinating tribes and cultures. From the San of Botswana and Namibia to the Kenya‘s Maasai and Ethiopia‘s Mursi, part of the continent’s fascination and intrigue lies in its people.

Not only can our travel designers incorporate ethical cultural visits within an itinerary, Rothschild Safaris also takes great consideration in the properties and locations we choose, adhering to those that support their local traditional communities, without exploit and upholding tradition.

Wherever your journey may take you, take the time to make cultural connections to enrich your safari experience.

Talk to our travel designers about discovering the tribal cultures of Africa and the world.